On April 2, 2020, three weeks

after declaring a nation-wide state of emergency and well behind the reporting curve

elsewhere, Malawi’s government publicly reported the country’s first cases of

the coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Within

that first week, 16 confirmed cases and two deaths were attributed to COVID-19.

In the last week of December 2020, the

rate of weekly infection was running at a reported 193 new cases, adding

to the now total 6,377 people infected and 188 deaths although, as in so many

countries, the full number of infections and deaths from the coronavirus disease

will probably never be known, in part because of low testing rates. But the ongoing rate of infection has been

concerning enough that on December 23, 2020, the authorities announced a 14-day closure of the landlocked

country’s international borders although shying away from an internal lockdown.

The move recognizes the importance of restricting connectivity and travel in containing or circuit-breaking the spread of the

disease, and borne out by several recent urban planning studies that weigh the impacts of urban density and

connectivity in transmission.

Malawi does not make it into the international news very often. A landlocked country in Central Africa, it is known, if at all, through its tourism byline as “the warm heart of Africa”. But compounding the alarming coronavirus news is that festering behind the warmth and friendliness shown to all travelers, is a people smitten by one of the highest poverty rates in the world and a history of poor governance that have meant little progress in addressing poverty and inequality over the past decades. And whilst a child born today might have a three-times greater chance of surviving to the age of five and a 17% higher probability of finishing primary school than if they had been born 15 years ago, GNI per capita remains an impossibly meagre US$380/year. Nearly three out of four Malawians somehow subsist on less than US$1.90 per day – insufficient to meet a basic daily calorie intake. In a country that is only 17 percent urbanized, rain-fed agriculture and fishing-based livelihoods are routinely afflicted by insect plagues and weather shocks such as droughts and floods which have been noticeably increasing in intensity and frequency due to climate change.

Add to this that Malawi and its neighboring

countries lie along the north-south trucking corridors through Africa and have

faced a multi-decades long HIV/AIDS epidemic.

By mid-2006, WHO was reporting HIV/AIDS as the leading cause of death in

the region amongst the productive age groups. Today, around 70 percent of

people in the world living with the disease are in Sub Saharan Africa. One in ten adults in Malawi are infected and

the country has anywhere between 500,000 (WHO) to two million orphans and

vulnerable children directly related the AIDS epidemic (see Paul Mkandawire’s

thoughtful “Vulnerability

of HIV/AIDS orphans to floods in Malawi”).

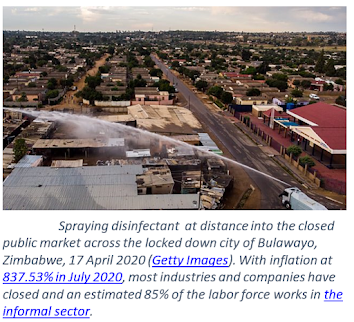

The ‘fifth-risk’ – the risk of an international viral outbreak that had been worried about by some but ignored by most, has swept across the globe in 2020. In less than four months, it had touched every country on the planet. Now, in December 2020, and after close to a year of the world learning to live with the coronavirus pandemic, we have all become armchair epidemiologists, but it is only the most perverse who continue to maintain that livelihoods vs. health is a binary choice. So, back in April 2020, when Malawi’s then ‘Tipp-ex President’ Mutharika announced a mandatory 21-day nationwide total lockdown that would close food markets and non-essential businesses, restrict hours for (outdoor) farming, and only allow health and emergency services workers to use public transport, it was not unsurprising to hear on international news stations that Malawi’s market vendors in Blantyre and Mzuzu were angrily protesting in the streets and that they had joined forces with the Human Rights Defenders Coalition to successfully challenge the lockdown order in court. Similar news stories of dramatically enforced total lockdowns have emerged from cities across the Global South from India to South Africa to Nigeria, highlighting the plight of informal and casual workers who form the majority of many of the countries’ workforces and who, even under pre-pandemic circumstances, faced daily food shortages and lived from hand to mouth with no buffer to weather shocks.

Throughout 2020, many countries –

rich or poor, democratic or centrally planned, large or small, led by women or

men, and densely or less densely settled have cautiously and responsibly managed

to find a balanced approach to protecting lives whilst at the same time stimulating

lower risk economic activities and providing profligate support to affected and

vulnerable groups. Countries such as

Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, South Korea, Japan, Vietnam, Germany,

Finland, Norway, Vanuatu, Samoa, Kiribati, and many more will have lessons for

all of us in the years to come, including of governments communicating clear

and unambiguous health messages and providing equitable basic services and

economic support measures, and of citizens being concerned for and helping

their own families and neighbors. For

every crazy that this year has thrown up, there have been countless examples of

resilience in action where countries, communities and individuals have embraced

measures “

to effectively manage their own layer of risk”.

At the time of writing this blogpost (December 2020), several countries - including wealthier ones with less enviable records of COVID-19 management, are developing policies and commencing vaccine delivery for healthcare and essential workers, vulnerable groups and the elderly. Populations are eagerly anticipating that safe and effective vaccines can be rolled out, for free, to those that want them over the coming weeks and months and in the hope that by mid-2021, life for people living in these countries might “return to normal”. We also know - but do not speak enough about, that vaccination roll out will be a logistical nightmare and will require recruitment and multi-year funding for huge numbers of trained health workers to administer the cold-stored vaccines. Widespread vaccinations in countries with the least buffers (including most of Sub Saharan Africa and South Asia) are unlikely to be available any time before 2024, even if funding were assured through the COVAX alliance (which it is not).